07 - Bilinear Transform¶

Lecture 07 - 11 October 2021

Approximations for the simulation theorem¶

In the previous lecture, a way to approximate a system \(\tilde{G}(s)\) or \(\tilde{G}(\omega)\) with a discrete transfer function was seen. The result obtained is that \(V(z)\) is a perfect simulator for \(\tilde{G}(\omega)\) if and only if \(\tilde{G}(\omega)=V(z=e^{-i\omega T})\). It’s now time to search for a general way to obtain the discrete \(\tilde{V}(z)\) starting from the transfer function \(\tilde{G}(\omega)\). A first way would be to invert \(z=e^{-i\omega T}\rightarrow \omega=\frac{i}{T}ln(Z)\) but that would introduce a branch cut on \(\mathcal{R}_{0}^{-}\). A possibility is to abandon the search for an exact inversion and use a sufficiently close approximation \(\tilde{V} = \tilde{G}(\omega=f(z)) + \mathcal{o}\left( w^n\right)\).

Case 1: \(sin(\omega t)\)¶

Let’s start by writing \(sin(\omega t)\) as an exponential:

And write the taylot series:

So that

Case 2: Bilinear Transform \(tan\left( \frac{\omega T}{2}\right)\)¶

Note: any function can be choosen to obtain the approximation but \(tan\left(\frac{\omega \pi}{2} \right)\) presents some nice features which will be discussed later.

Note 2: \(V(z)=\tilde{G}_{\mathcal{F}}\left(\omega=\frac{2i}{T} \frac{z-1}{z+1}\right) = \tilde{G}_{\mathcal{L}}\left(s=\frac{2}{T} \frac{z-1}{z+1}\right)\) is expected to be a good approximation of \(\tilde{G}_{\mathcal{F}}(\omega)=\tilde{G}_{\mathcal{L}}(s)\) if \(\omega T << 1\) i.e. if \(T_{SAMP}<< \frac{1}{\text{frequencies of interest}}\).

Bilinear transform and its properties¶

Let’s now see what happends when we apply a bilinear transform to a rational function:

Reality¶

Reality is conserved

As we know that an analog system is real \(\iff\ \tilde{G}^*(\omega)=\tilde{G}(-\omega)\) we have proven the statement.

Causality¶

Causality can be proven but the proof is long and tedious. Just assume causality a priori or check the conditions \(0\not \in ROC; \infty \subset ROC\).

Bibo Stability¶

Reminder: An analog system is bibo stable \(\iff \mathcal{Re}\{poles\}<0\).

Reminder 2: A rational system can always be decomposed in a sum of fractions:

and the poles stays of the same order after a bilinear transformation. It’s now possible to prove the preservation of bibo stability:

by imposing \(\mathcal{Re}\{poles\}<0\) one obtains \(\left| z_0 \right|<1\), that is, all the poles \(\subset \Gamma_1\). As all the poles are strictly under \(\Gamma_1\) it is possible to find a curve that includes all the poles, is contained in \(\Gamma_1\), and encloses \(+\infty\). This implies that the system is Bibo stable. Another reason for which bilinear is preferred is that it is well-behaved near the boundaries of the Nyquist band:

Assume \(N>M\) (this can always be done by renaming eventual derivatives in the transfer function)

The term \((z+1)^{N-M}\) is a leading term. Now let’s replace the simulation theorem:

That is, the tails of \(\tilde{x}(\omega)\) are smoothed out near the boundaries of the Nyquist band and ensure a nice transition to the cut region.

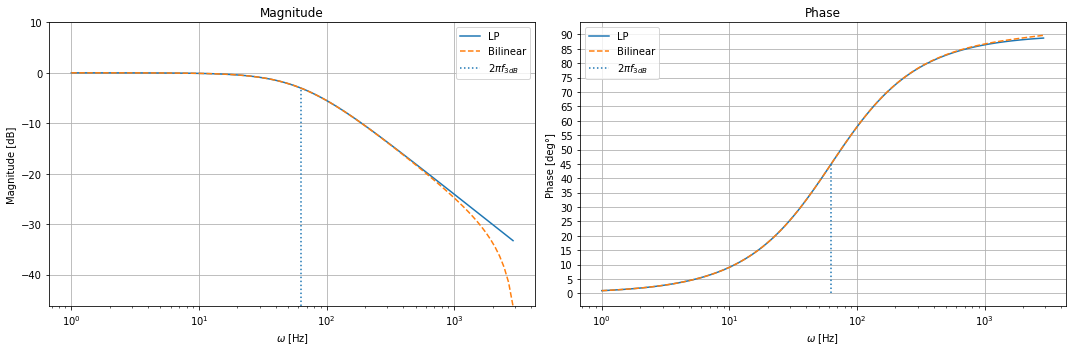

e.g. LOW PASS (actual implementation)¶

Let’s now plot the Bode diagram for a low pass an for its bilinear transform. The two equations of interest are:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

##############

# PARAMETERS #

##############

T=1/1024 # Sampling time

omega = np.logspace(start=np.log10(1), stop=np.log10(0.9*np.pi/T), \

num=100, endpoint=True, base=10.0)

f3dB = 10 # Hz

omega0=2*np.pi*f3dB

tau = 1/(2*np.pi*f3dB)

#print("T=\t{:e}\ntau=\t{:e}".format(T, tau))

##################

# IDEAL LOW PASS #

##################

lp = 1/(1-1j*omega*tau) # Ideal Low pass

mag_lp = 20*np.log10(np.abs(lp))

phase_lp = np.arctan(np.imag(lp)/np.real(lp))*180/np.pi

######################

# BILINEAR TRANSFORM #

######################

c = (1-T/(2*tau) ) / (1+T/(2*tau) )

lp_bt = 0.5*(1-c)*( np.exp(-1j*omega*T)+1 ) /(np.exp(-1j*omega*T)-c)

mag_lp_bt = 20*np.log10(np.abs(lp_bt))

phase_lp_bt = np.arctan( np.imag(lp_bt)/np.real(lp_bt))*180/np.pi

#########

# PLOTS #

#########

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(15, 5))

ax[0].semilogx(omega, mag_lp, label="LP") # Bode magnitude plot

ax[0].semilogx(omega, mag_lp_bt, "--", label="Bilinear") # Bode magnitude plot

ax[1].semilogx(omega, phase_lp, label="LP")

ax[1].semilogx(omega, phase_lp_bt, "--", label="Bilinear")

ax[0].vlines(omega0, min(mag_lp_bt), 20*np.log10(np.abs(1/(1-1j))),linestyles=":", label=r"$2\pi f_{3dB}$")

ax[1].vlines(omega0, 0, 45, linestyles=":", label=r"$2\pi f_{3dB}$")

ax[0].set_title("Magnitude"); ax[1].set_title("Phase")

ax[0].set_xlabel(r"$\omega$ [Hz]"); ax[0].set_ylabel(r"Magnitude [dB]");

ax[1].set_xlabel(r"$\omega$ [Hz]"); ax[1].set_ylabel(r"Phase [deg°]");

ax[0].grid(); ax[1].grid()

ax[0].legend(); ax[1].legend()

ax[1].set_yticks([x for x in range(0, 91, 5)])

ax[0].set_ylim([min(mag_lp_bt), 10])

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()